Jonathan Neville’s latest folly: The Kinderhook Plates

|

Tags: Archeology, Historical sources, Kinderhook Plates, Misrepresentation, Responsible scholarship

Heartlanders have a tendency to accept archaeological hoaxes as genuine artifacts. The Michigan Relics (which James E. Talmage debunked over 100 years ago), the Newark Holy Stones and the Los Lunas Decalogue Stone (see here), and the Tucson Lead Artifacts (see here) have all been exposed as modern frauds, yet Heartlanders claim they are legitimate evidence of ancient Book of Mormon peoples in North America.

(This very day, in fact, The Salt Lake Tribune published an article about the Heartland movement. The article quotes Kenneth Feder, who holds a Ph.D. in anthropology and has taught that subject at Central Connecticut State University since 1977. Regarding the Newark Holy Stones, Feder says, “Archaeologists are certain it’s a hoax. Case closed.”)

Recently, Jonathan Neville sat for a half-hour interview on YouTube in which he described the history of the Kinderhook Plates and the supposed evidence for their authenticity:

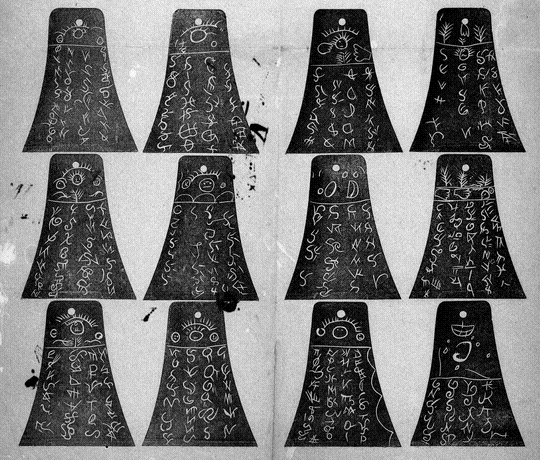

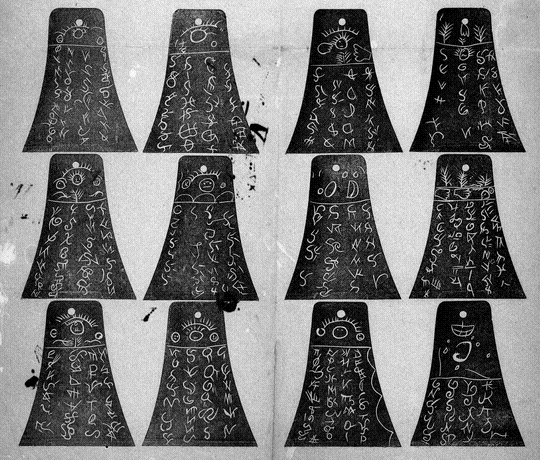

A facsimile of the Kinderhook Plates, published by John Taylor in the Times and Seasons, May 1, 1843. (Click to enlarge.)

The Kinderhook Plates were an attempted hoax perpetrated on the Prophet Joseph Smith. As the Church’s article about the plates explains, a group of men brought the six small, engraved, bell-shaped plates to Joseph in 1843. Joseph initially showed some interest in the plates, but he never produced a revealed translation of them.

In 1878, Wilburn Fugate claimed that he and two other men created the plates “simply for a joke.” Questions about the authenticity of the plates persisted until 1980, when Stanley B. Kimball secured permission from the Chicago Historical Society to have Northwestern University perform destructive tests on the one extant plate from the set. The findings of those tests were published in the August 1981 edition of Ensign magazine. Kimball wrote:

With regard to the scientific tests that have been performed on the plates, Neville specifically said (beginning at 9:16):

So, contrary to Neville’s glib claim that Stanley Kimball just “assumed” that the plate was made in the 1800s because of the composition of the alloy, the tests performed at Northwestern University in 1980 provided practically incontrovertible evidence that the Kinderhook Plates could not have been made anciently. There is no “ambivalence,” as Neville claims.

This yet another example of Neville misrepresenting the evidence so that it fits his predetermined beliefs. It’s to Neville’s advantage if the Kinderhook Plates are genuine, because that would mean they were discovered in the American Midwest and are of Jaredite origin, therefore proving the Heartland theory. He’s content to overlook historical and scientific evidence just to reinforce his personal beliefs.

—Peter Pan

(This very day, in fact, The Salt Lake Tribune published an article about the Heartland movement. The article quotes Kenneth Feder, who holds a Ph.D. in anthropology and has taught that subject at Central Connecticut State University since 1977. Regarding the Newark Holy Stones, Feder says, “Archaeologists are certain it’s a hoax. Case closed.”)

Recently, Jonathan Neville sat for a half-hour interview on YouTube in which he described the history of the Kinderhook Plates and the supposed evidence for their authenticity:

A facsimile of the Kinderhook Plates, published by John Taylor in the Times and Seasons, May 1, 1843. (Click to enlarge.)

In 1878, Wilburn Fugate claimed that he and two other men created the plates “simply for a joke.” Questions about the authenticity of the plates persisted until 1980, when Stanley B. Kimball secured permission from the Chicago Historical Society to have Northwestern University perform destructive tests on the one extant plate from the set. The findings of those tests were published in the August 1981 edition of Ensign magazine. Kimball wrote:

The extreme depth of focus and resolution of the scanning electron microscope (SEM) at high magnification make it possible to clearly distinguish between etching or engraving on metal surfaces. If a character were cut or scratched into the surface, the groove would contain secondary grooves and ridges running lengthwise within it where the engraving instrument forced a flow of metal. This would be especially noticeable at groove intersections, where metal would be pushed from the second groove into the first. On the other hand, etched lines would show no metal flows or secondary grooves; instead, a roughened, pock-marked etching would be seen.… The irregular, grainy texture characteristic of acid etching is evident, not a striated surface that would have been produced by an engraving tool.…Kimball’s findings match those of a non-destructive examination of the plate performed in 1966 by Latter-day Saint physicist George M. Lawrence, who concluded:

The X-ray fluorescence test indicated that the plate was made of a true brass alloy of approximately 73 percent copper, 24 percent zinc, and lesser amounts of other metals. In addition, an examination of the small area of the plate that was ground and polished revealed a basically “clean” alloy—that is, there were very few visible traces of impurities such as particles of slag and other debris that one might expect to find in metal of ancient manufacture.

As a result of these tests, we concluded that the plate owned by the Chicago Historical Society is not of ancient origin. We concluded that the plate was etched with acid; and as Paul Cheesman and other scholars have pointed out, ancient inhabitants would probably have engraved the plates rather than etched them with acid. Secondly, we concluded that the plate was made from a true brass alloy (copper and zinc) typical of the mid-nineteenth century; whereas the “brass” of ancient times was actually bronze, an alloy of copper and tin. Furthermore, one would expect an ancient alloy to contain larger amounts of impurities and inclusions than did the alloy tested.

The metal of the plate is fine grained and homogeneous as are modern metals. It has no spring when flexed, like annealed copper. Except for scratches, the surface is smooth as if the plate had been rolled or ground rather than hammered or cast.…Despite the confession of Wilburn Fugate, the overwhelming scientific evidence, and the stated position of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Neville in his interview repeatedly claimed that the Kinderhook Plates were more likely to be authentic ancient relics than 19th-century forgeries.

The [plate’s] dimensions, tolerances, composition and workmanship are consistent with the facilities of an 1843 blacksmith shop and with the fraud stories of the original participants.

With regard to the scientific tests that have been performed on the plates, Neville specifically said (beginning at 9:16):

Well, Edward [sic] Kimball did an analysis. They took—there was one plate found—all the plates were lost, but as you [the interviewer] mentioned, the one plate had been discovered, and they knew it was the same one because there was the same etching and there was a nick on one of the corners. And so they did a metallurgical analysis and determined that it was an alloy that was common in the 1800s. And so, therefore, they assumed that it really was.Not only has Neville misrepresented the scientific analyses performed on the plates, it’s not even clear that he has more than a cursory understanding of the evidence and the arguments involved.

And they looked at the engravings, and the guy—sorry I’m not using their names, but people who don’t care [sic] what their names are, they can look it up in Wikipedia—but the guy who claimed it was a fraud [i.e., Wilburn Fugate] said that they etched it with acid, wax and acid. And, according to this metallurgical analysis, it was etched with acid, these things [points to the engravings on his replica of the Kinderhook plates]. But, at the same time, the original story was that they [the people who discovered the plates] washed it with acid. So, if they had washed it with acid, it could have caused the same kind of indication on the marks as being etched by acid. So, there’s a little bit of ambivalence.

- The individual who arranged for the tests to be performed in 1980 was Stanley Kimball, not Edward Kimball.

- The metallurgical tests done didn’t just determine that the plate was made from “an alloy that was common in the 1800s.” It determined that it was impossible for that alloy to be ancient, due to its high zinc content. Ancient copper–zinc alloys were composed of, at most, 15% zinc (Craddock & Lang, p. 217), while the Kinderhook plate analyzed by Northwestern University was made of 24% zinc, a percentage common for brass made in the 1800s.

- Likewise, the purity of the tested plate’s alloy—meaning its low amount impurities and debris—is what one would find in a brass alloy of modern manufacture. Ancient alloys, created by hand with rudimentary tools and equipment, had much higher amounts of slag than what we find in the plate tested in 1980.

- Furthermore, as George Lawrence’s analysis revealed, the surface of the plate is “smooth as if the plate had been rolled or ground rather than hammered or cast,” as it would have been if it were created anciently.

- Neville is also incorrect in claiming that washing the plate with acid could make it appear as if it were engraved with acid. As the scanning electron microscope analysis revealed, the engravings do not show any evidence of having been cut or scratched into the plate with a tool; rather, their texture is characteristic of acid etching.

So, contrary to Neville’s glib claim that Stanley Kimball just “assumed” that the plate was made in the 1800s because of the composition of the alloy, the tests performed at Northwestern University in 1980 provided practically incontrovertible evidence that the Kinderhook Plates could not have been made anciently. There is no “ambivalence,” as Neville claims.

This yet another example of Neville misrepresenting the evidence so that it fits his predetermined beliefs. It’s to Neville’s advantage if the Kinderhook Plates are genuine, because that would mean they were discovered in the American Midwest and are of Jaredite origin, therefore proving the Heartland theory. He’s content to overlook historical and scientific evidence just to reinforce his personal beliefs.

—Peter Pan

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Thoughtful comments are welcome and invited. All comments are moderated.